Creating Extensible Applications with MAF (System.AddIn)

Last month, my colleague, Pinku Surana, wrote an article about .NET AppDomains and how they can be used to provide component isolation and make your applications more reliable. If you missed it, you can read the Developments archives on Developmentor’s website. This month, I’d like to continue exploring reliability and extensibility by introducing you to a new framework included with .NET 3.5: The Managed Add-in Framework (MAF), sometimes referred to as System.AddIn.

The hardest part about this process was understanding how we could integrate the app as an Enterprise solution. Thankfully, there is a lot of information out there, such as the Salesforce application development process which aided us in understanding the barriers we had to beat.

Developers (and managers) have long desired a way to easily create extensible applications that allow new features to be added without jeopardizing the stability of the existing code base. The .NET framework has provided the underlying support to accomplish this from the very beginning through the reflection API and AppDomain support Pinku examined last month. MAF builds on that fundamental support to provide a higher-level service that allow you to dynamically discover, load, secure and interact with external assemblies used to provide features for your application. Several common architectural requirements are made trivial with MAF:

- Isolate aspects of your code for security reasons or partial-trust scenarios.

- Allow business partners to extend your application safely without access to the source code; Adobe Illustrator is a great example of this style of application.

- Separate volatile sections of your application out – where depending on the customer the application needs to execute different sets of code.

- Add or change code without unloading the application – for example pay-to-play scenarios, or where you need to update an assembly but the application must continue to run.

- Develop and evolve different sections of the application in parallel without any fear of destabilizing one based on the other.

If any of these scenarios sound like something you could utilize in your application then you should know about MAF!

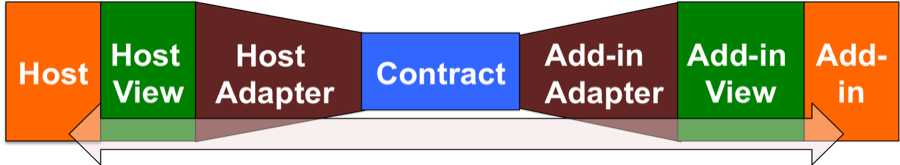

At the center of the MAF-based application is the pipeline.

The Pipeline

Communication between add-ins and the host application is strictly regulated by the pipeline. The pipeline is dynamically created by MAF through a set of loosely-coupled components which are used to version, marshal and transform the data as it passes back and forth between the host and each loaded add-in.

Each section of the pipeline is contained in a separate assembly, loaded as necessary to manage the specific add-in. MAF discovers each component and then loads them on request using reflection.

For reliability, MAF allows optional isolation boundaries to be created between the add-in and host – everything to the left of the contract is loaded into the main (host) AppDomain and everything to the right loaded into a newly created AppDomain which has its own security permission set. The isolation can also be done through cross-process calls if true process-level isolation is necessary. Under the covers, the system uses traditional remoting calls to do the work of marshaling calls back and forth.

Breaking down the pipeline, there are three main parts starting in the center with the contract.

Contract

As you might expect, MAF is based on interface contracts. Interfaces allow classes in an application to be loosely coupled, reducing the risk when changes are made between dependent sections of the code. The interface contract is shared between the host and add-in and once it has been established, it should never be changed.

Consider the simple example of a translator program. The host will expect to load one or more translator add-ins that will do some work on an inbound string and return the results. To accomplish this, I might create an ITranslator interface that looks like:

[AddInContract]

public interface ITranslator : IContract

{

string Translate(string input);

}

Notice that the interface derives from IContract. This is a requirement for add-in contracts and is what will be used to provide marshalling support when the pipeline is established. We also need to decorate the interface with the [AddInContract] attribute – this is the marker used by MAF to identify the contract when it is dynamically constructing the pipeline. Both of these types come from the System.AddIn.Pipeline namespace in System.AddIn.Contract.dll.

Views

Moving to the edges, we find the views. This is the code that the add-in and host directly interact with. It represents a host or add-in specific “view” of the contract and, like the contract, is contained in a separate assembly.

Both of the view classes will echo the structure of the contract, but not actually be dependent upon the contract. For example, our host side view might look like this:

public abstract class TranslatorHostView

{

public abstract string Translate(string input);

}

The view is commonly exposed as an abstract class to make it look more natural when used by the host, but an interface will work just as well. The host uses the view directly when communicating with any add-in based on the contract.

On the add-in side, we have an almost identical class – except we decorate this type with the [AddInBase] attribute so MAF knows which side of the pipeline this view is for (the add-in). This is located in the System.AddIn.Pipeline namespace in the System.AddIn assembly.

When we create each add-in, the implementation will use this type as the base class.

[AddInBase]

public abstract class TranslatorAddInView

{

public abstract string Translate(string input);

}

Adapters

The last piece of the pipeline is the adapters. The adapters play a very special role in the pipeline – they are the glue that binds the contract to the view: implementing lifetime management and any necessary data conversion between the two ends.

It may seem redundant to have this class, but by separating the view from the contract we introduce version tolerance into our architecture – the host can version independently of the add-in and vice-versa. Depending on the situation, the adapters can be as simple as a pass-through class, or can provide higher-level services to allow non-serializable types to be marshaled across the isolation boundaries.

On the host side, the adapter will implement the view (remember it is either an interface or abstract class). It will be passed a reference to the contract in the constructor and it is responsible for connecting the two together.

[HostAdapter]

public class TranslatorHostViewToContract : TranslatorHostView

{

ITranslator _contract;

ContractHandle _lifetime;

public TranslatorHostViewToContract(ITranslator contract)

{

_contract = contract;

_lifetime = new ContractHandle(contract);

}

public override string Translate(string input)

{

return _contract.Translate(input);

}

}

In this simple example, the code caches off the contract interface. This is a remoting proxy to the actual loaded add-in. The adapter then implements the Translate method and passes it forward to the contract for implementation. If we had non-serializable types, then the adapter would be responsible for converting them into something that was serializable.

It also provides some lifetime management for the contract. Because the contract is a remoting proxy and is likely running in a separate AppDomain (or even process) we have to be concerned with how long it lives. MAF provides all the support for this through the ContractHandle class. Most of the time, all you will need to do is store a ContractHandle in your host adapter and then pass it the inbound contract to wrap in your constructor.

Finally, in order for MAF to identify this class, it must be decorated with the [HostAdapter] attribute from the System.AddIn.Pipeline namespace out of the System.AddIn.dll.

The add-in side looks very similar, but does the opposite: it makes the add-in view look like the contract.

[AddInAdapter]

public class TranslatorAddInViewToContract : ContractBase, ITranslator

{

TranslatorAddInView _view;

public TranslatorAddInViewToContract(TranslatorView view)

{

_view = view;

}

public string Translate(string input)

{

return _view.Translate(input);

}

}

MAF passes the view to the constructor and the class caches the reference off in a field. It implements the contract (ITranslator) and ContractBase which provides the implementation of the IContract interface for us (remember this was a required interface on our contract). As the host makes calls to the contract interface, this class will translate those calls to the add-in view, which as you will see is the implementation provided by the add-in itself. Note how the [AddInAdapter] attribute is used to mark this class so MAF can discover it.

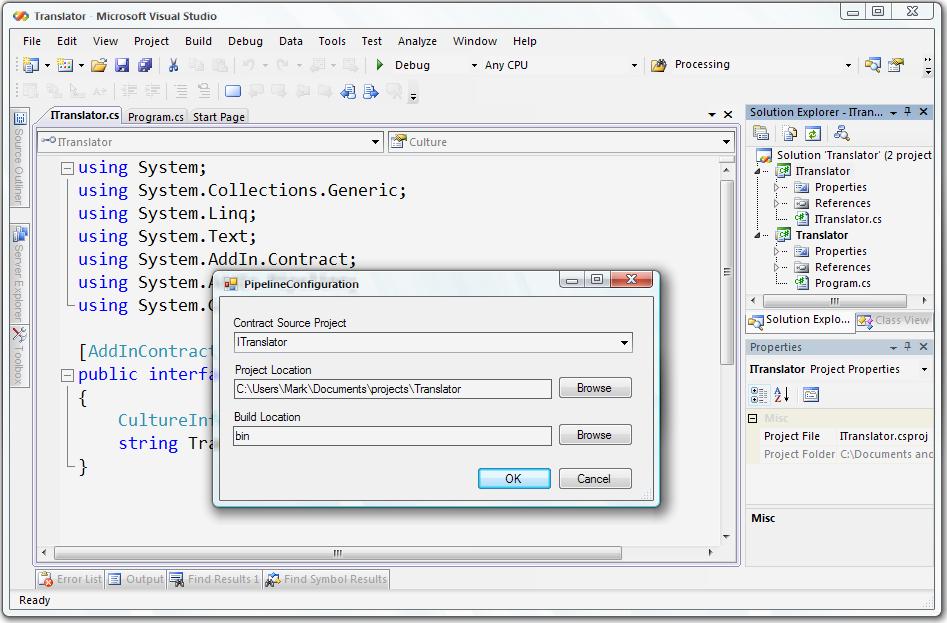

If it seems like all the above is a lot of repetitious, boilerplate code well.. you’re right! To make it easier on the developer to create the pipeline components, the MAF team has created a pipeline builder available at http://www.codeplex.com/clraddins. It takes the contract assembly and then generates the views and adapters from it:

Creating an add-in

Once the pipeline pieces are built you can create add-ins. Each add-in provides an implementation of the abstract add-in view. For example, we might provide a BabelFish add-in for universalized translation:

[AddIn(“BabelFishTranslator”, Description=“Universal translator”, Version=“1.0.0.0”, Publisher=“Zaphod Beeblebrox”)]

public class BabelFishAddIn : TranslatorAddInView

{

public string Translate(string input)

{

...

}

}

The add-in implements the AddInView, providing a concrete implementation of the Translate method. It is decorated with the [AddIn\] attribute that allows it to provide a name, version, description and other data the host can use to decide whether it is a useful translator.

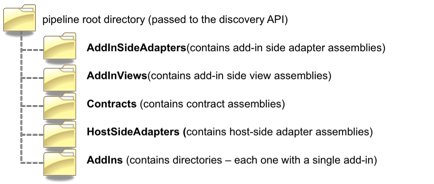

Putting the pieces together – the directory structure

To properly identify each of the components necessary, MAF enforces a particular directory structure you need to follow for deployment. Each piece is stored in a sub-directory off the root of the pipeline directory (this is typically the APPBASE where the host executable is stored).

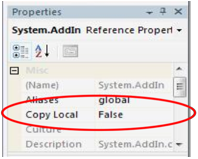

The directory names are required, but not case sensitive – each directory holding a single piece of the pipeline that MAF will load dynamically when it is loading the add-in. The host-side view is always located in the same directory as the host executable itself so it does not need a dedicated directory. When creating your Visual Studio project, it is important to set the output directories appropriately so that you create the above directory structure. In addition, all references between the components should be marked as CopyLocal = “false” in Visual Studio to ensure a local copy of the assembly isn’t placed into the sub-directory:

Discovering and loading add-ins from the host

The last piece of the puzzle is the actual loading of add-ins from the host. This is done in three basic steps:

- Identify and catalog the add-ins

- Retrieve the list of specific add-ins based on view or name

- Activate and use the add-in

The first step is to identify the available add-ins for the host. This is done through the System.AddIn.AddInStore class:

string[] errorList = AddInStore.Rebuild(PipelineStoreLocation.ApplicationBase);

Calling Rebuild forces MAF to walk the directory structure and create the pipeline database. It stores this information in the pipeline root directory and returns a list of errors, if any occur. The most common errors are missing pipeline components – where MAF is unable to locate some required portion of the pipeline such as a View or Adapter.

Next, the host will retrieve a list of add-ins based on the host view through the FindAddIns method – these will be the add-ins conforming to a specific contract (whatever the view/adapter is bound to):

Collection addinTokens = AddInStore.FindAddIns(typeof(TranslatorHostView), PipelineStoreLocation.ApplicationBase);

The first parameter is the host view type – so MAF knows what add-ins we are looking for, the second is the pipeline root directory, which is the same directory passed to the Rebuild method and indicates where the pipeline database is stored.

The returning collection represents a series of tokens that are used to identify and control the add-ins. This is how the host can examine, activate and unload the add-in. To activate a specific add-in, you can take the token and call Activate:

Collection addinTokens;

...

foreach (AddInToken token in addinTokens)

{

TranslatorHostView view = token.Activate(AddInSecurityLevel.Internet);

string hello = view.Translate(“Bonjour”);

...

}

The Activate call loads all the required components, instantiates the add-in type and returns the host view used to interact with the add-in. Calls made to this object will be marshaled back and forth to the add-in using the pipeline.

Notice that the parameter passed to Activate indicates the security level required. There are several overrides that allow you to dictate exactly how the add-in is loaded. You can load the add-in into a specific AppDomain – the current one for best performance:

token.Activate(AppDomain.CurrentDomain);

You can specify a specific permission set to restrict the things the add-in can do on your behalf:

PermissionSet pset = ...;

token.Activate(pset);

Or you can specify a known permission set based on the CAS zones:

Once the add-in is activated, the host can call it just like any other object – but never forget that you are likely crossing an isolation barrier! Make sure to design your contracts so that you minimize the number of calls between the host and add-ins to ensure your performance doesn’t suffer.

When you are finished with the add-in, you can tell MAF to unload it through the AddInController associated with the view:

AddInController ctrl = AddInController.GetAddInController(view);

ctrl.Shutdown();

This will unload the add-in side pipeline and then destroy the containing AppDomain so you release the resources associated with it.

There are many other capabilities MAF provides such as versioning, passing collections and WPF visuals, passing non-serializable types, etc. You can get a pretty decent overview of the features from MSDN and the MAF team has a blog at http://blogs.msdn.com/clraddins/ that has some great, practical information on using this new framework.