Part 1: It's Basically Focus

Focus Types

As you may know, in WPF there are two types of focus: logical focus and keyboard focus.

Keyboard focus is the easiest to grasp: the element with keyboard focus is where any keystrokes will end up. Only one element can have keyboard focus at any particular time, and it’s possible that no element currently has keyboard focus (this happens most commonly when the application itself is not the activated application).

Logical focus is a little murkier. Logical focus represents where keyboard focus could go within a group of elements. There may be multiple elements with logical focus within the application and one of them likely has keyboard focus. Having keyboard focus automatically indicates logical focus but not vice-versa.

This distinction is modeled after Win32 itself – each thread has one HWND it has identified to have focus but only one of them really has input focus at any given point in time.

In WPF, logical focus is tracked and managed by a Focus Scope. A focus scope is created by certain elements to keep track of which element should have focus. There can be multiple focus scopes within the application – each identifying a single element that has logical focus. Focus scopes are created and managed by the FocusManager class. It exposes two attached properties and the requisite static method wrappers to access them:

IsFocusScope - determines whether the current object is a focus scope. FocusedElement - returns which element child of the given focus scope object has logical focus.

It also exposes a handy method to find the focus scope for a given element - GetFocusScope

So what creates a focus scope and why do we need more than one? Well, the elements in WPF that create focus scopes by default are Window, Menu, ContextMenu and ToolBar. The reason we need more than one is to ensure your application works the way you expect it to. When you are typing in a TextBox and click a menu item, you really want focus to return to the original TextBox once the menu is dismissed. That’s focus scopes in action – the Window maintains logical focus in the TextBox and when you click on the menu, keyboard focus shifts to the menu. Since it maintains its own focus scope, it has its own logically focused element that WPF sets focus to (the menu and menu items in this case). Once you shift back to the window, keyboard focus moves back to that focus scope’s logical focus: the text box. Without focus scopes to track the original focus holder, WPF wouldn’t know where focus should go.

Focus scopes are also critical to command routing – often execution of commands depends upon focus. Some commands become active because a specific control which has a handler for the command has focus. Without focus scopes, we could not have menu items and toolbar buttons initiate those commands – they would steal focus away from the target, making the command unavailable. However, when WPF encounters a focus scope it checks the element that has logical focus in that scope to see if it can handle the command. If not, the command continues routing up to the parent of the focus scope.

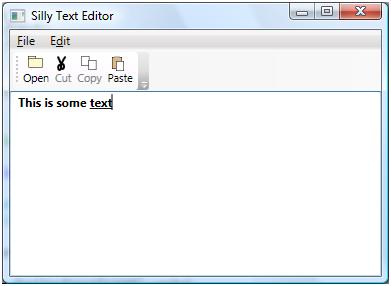

To show all of this behavior, I have rigged up a sample application with two windows. The first is a traditional text editor window with a menu and toolbar and a RichEdit control for the content. It looks like:

Forgive my 5-minute graphics for the buttons – I just threw them together in Visual Studio, a real project would use Blend to generate the graphics.

Regardless of it’s look, the application functions the way you expect – you can type in the text field, click buttons and select menu choices to Open, Cut, Copy and Paste content. The Cut/Copy/Paste commands are only available when the TextBox is in the appropriate state:

Cut: TextBox has focus and has some text selected. Copy: TextBox has focus and has some text selected. Paste: TextBox has focus and text exists on the clipboard.

This is all an artifact of the routed command system in WPF – the TextBox has command handlers registered for ApplicationCommands.Cut, ApplicationCommands.Copy and ApplicationCommands.Paste and when it has focus (and the above criteria is met) those commands could be executed.

When you click on a button or a menu choice, it executes the command it is associated with and WPF decides which handler should be called. This normally involves walking the visual tree:

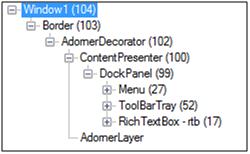

In this case, if the menu item for “Cut” were selected, it would start looking at the menu, then move up the tree consulting each parent and looking for a CommandBinding to handle the command. If that were the whole story then the Cut command would never happen because nothing in the visual tree above the menu has a binding to execute the Cut command. But, of course, it’s not the whole story – in this case, WPF sees that the Window is a focus scope and so it gets the logically focused element from the Window and looks for a CommandBinding there. That happens to be our RichTextBox – which is where the command ultimately gets handled.

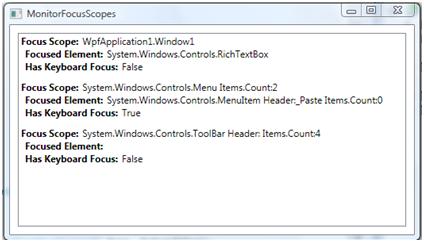

To see all of this in action, the second part of the application is a focus scope monitor window.

It shows all the known focus scopes and what the active focused element is, as well as whether that element has keyboard focus. The window is live so as you click around in the text editor you can see focus shifting and changing. The element with keyboard focus is the Paste menu item – notice that the rich text box is the logically focused item for “Window1” but does not have keyboard focus. Once you select the menu choice (or cancel) then keyboard focus shifts back to Window1 which assigns it to the RichTextBox.

If you’d like to play with this sample, you can get the full source code here.

In the next blog post, I’ll write about how you can programmatically assign and control focus in code and XAML.