MVVM: Views and ViewModels

In the previous post, I provided a link to the project template you can use to start a new MVVM project using the JulMar MVVM library. Here’s the two links in case you didn’t get them before:

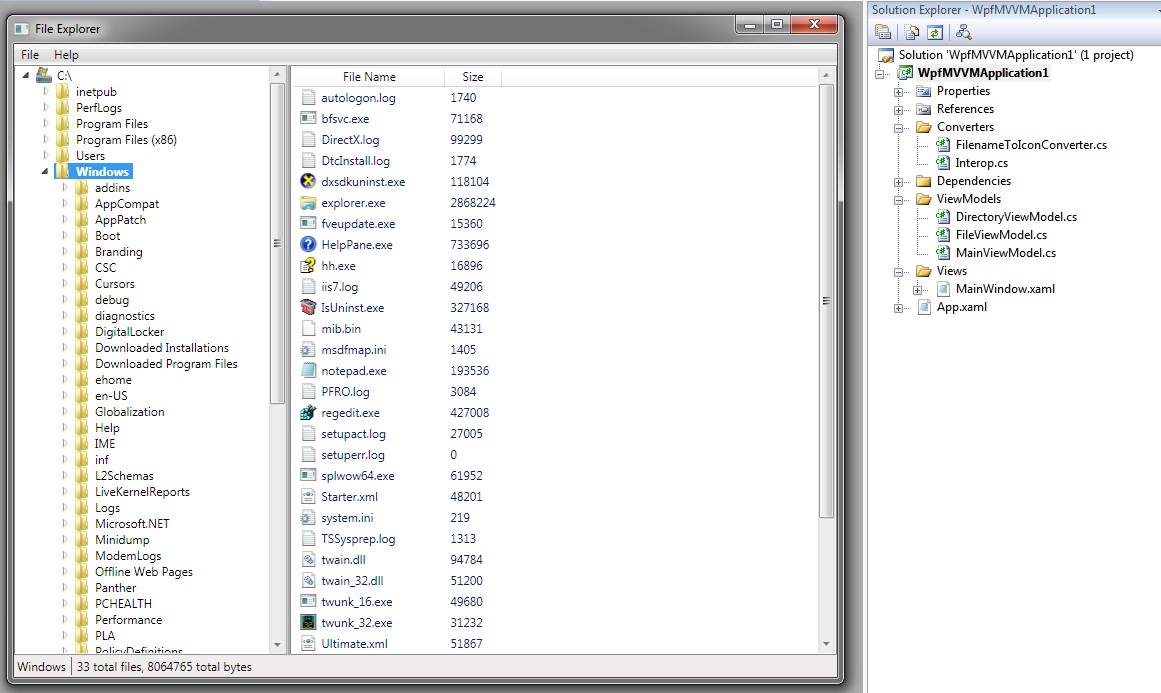

Copy the project template into your Visual Studio templates directory located off your user documents. Ok, so once you have these installed, what can you do with them? Well, for starters, you can now generate a starter project that provides a nice template for an MVVM application. The starter template creates a simple “Explorer” like program - it looks like this:

Notice there are two sections - a TreeView listing all the directories, and a ListView showing all the files in the selected directory. Let’s look a little closer at the project structure. There are four directories in the solution:

- Converters: This has a simple ValueConverter that takes a filename and returns an icon as an ImageSource.

- Dependencies: This is the binary dependencies the project requires, specifically it contains the JulMar MVVM libraries and Blend action libraries.

- ViewModels: This directory contains all the business logic in the form of ViewModels.

- Views: Finally, this directory contains all the UI (XAML) for the application.

Views

Let’s start with the last folder - the Views. Views are the UI presentation of data - in the case of a WPF/Silverlight application this is most commonly the XAML and XAML code behind files (they are considered a single element together). We want to have UI-specific code and designer elements present in these files. Generally we prefer to place business logic and testable elements into the ViewModel area.

In this starter project, we have a single view MainWindow.xaml. This is what presents the main UI shown above. The code behind file contains the required boilerplate code (essentially a constructor and call to InitializeComponent).

If you open the view (note that the designer will choke on it until you compile the project), you will find fairly straightforward XAML that creates the UI, let’s break it down as we go:

<Window x:Class="WpfMVVMApplication1.Views.MainWindow"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

xmlns:julmar="http://127.0.0.1:8080/wpfhelpers"

xmlns:ViewModels="clr-namespace:WpfMVVMApplication1.ViewModels"

xmlns:Converters="clr-namespace:WpfMVVMApplication1.Converters"

DataContext="{julmar:ViewModelCreator {x:Type ViewModels:MainViewModel}}"

Title="File Explorer" Height="400" Width="500">

First, notice how the DataContext is established – through a custom MarkupExtension called ViewModelCreator. This extension is responsible for creating an associated ViewModel for this view (where our testable business logic should go) and also wiring up a couple of special event handlers that will allow the ViewModel to activate the view and close the view respectively.

Next, let’s check out the resources:

<Window.Resources>

<!-- Bindable commands sit in resources and allow keyboard input to target ViewModel commands -->

<julmar:BindableCommand x:Key="CloseCommand" Command="{Binding CloseAppCommand}"/>

<Converters:FilenameToIconConverter x:Key="iconConverter"/>

<HierarchicalDataTemplate x:Key="DirectoryTemplate" ItemsSource="{Binding Subdirectories}">

<StackPanel Orientation="Horizontal">

<Image Width="16" Height="16" Source="{Binding FullName, Converter={StaticResource iconConverter}}"/>

<TextBlock x:Name="tb" Margin="5,0" Text="{Binding Name}"/>

</StackPanel>

<HierarchicalDataTemplate.Triggers>

<DataTrigger Binding="{Binding IsSelected}" Value="True">

<Setter TargetName="tb" Property="FontWeight" Value="Bold"/>

</DataTrigger>

</HierarchicalDataTemplate.Triggers>

</HierarchicalDataTemplate>

</Window.Resources>

Here we find three defined resources – first we have a JulMar MVVM BindableCommand. This is a special ICommand instance that can be data bound and forwards to the specified binding. We use this a bit later in the keyboard accelerator to close the application. Next, there is the converter that takes a filename and converts it to an icon – that’s the source code in the Converters folder mentioned earlier. I use a converter here because this is very UI-centric and not very testable – so the converter will data bind to a string (filename) property of the ViewModel and retrieve the icon for the UI to display. That way, my ViewModel sticks with base (non-WPF) types. This isn’t a hard rule – but it’s a good one to try to follow.

Finally, there is a DataTemplate that is used to display the directory structure – this is what the TreeView uses to display it’s data. Notice it data binds to a couple of properties – FullName, Name and IsSelected. All of these, as you will see, exist in our ViewModel definition. The View takes the data from the ViewModel and displays it onto the UI for the user to interact with.

Next in the XAML is the input bindings – this is where we define keyboard and mouse gesture accelerators, and it’s where I use the bindable command I defined earlier:

<Window.InputBindings>

<KeyBinding Key="X" Modifiers="ALT" Command="{StaticResource CloseCommand}" />

</Window.InputBindings>

Here you can see that instead of trying to bind to the command, we use {StaticResource} to get it from the resources. This is necessary under WPF 3.5 because the KeyBinding will not inherit the DataContext and so cannot bind directly to the command – but resources can, and specifically Freezable resources can – that’s what the BindableCommand provides – a Freezable resource that forwards the ICommand implementation onto a command defined in the DataContext ViewModel. This is not necessary under WPF4 – this is actually one of the new features they’ve added: to inherit the DataContext in your input bindings!

The remainder of the view is fairly traditional – we use bindings to connect the UI up to the ViewModel definitions, so let’s go look at what those are.

ViewModels

The ViewModel folder contains three source code files – DirectoryViewModel.cs, FileViewModel.cs, and MainViewModel.cs. If you recall from above, MainViewModel is the primary ViewModel that is data bound to the view. The other two are child view models used to represent the files and folders respectively. Let’s look at FileViewModel as an example:

public class FileViewModel : SimpleViewModel

{

/// <summary>

/// Marker file that signals expansion of the tree.

/// </summary>

internal static FileViewModel MarkerFile = new FileViewModel();

private readonly FileInfo _data;

/// <summary>

/// File name

/// </summary>

public string Name

{

get { return _data.Name; }

}

/// <summary>

/// Full path + filename

/// </summary>

public string FullPath

{

get { return _data.FullName; }

}

/// <summary>

/// Size of the file in bytes

/// </summary>

public long Size

{

get { return _data.Length; }

}

/// <summary>

/// Private constructor used to create marker file.

/// </summary>

public FileViewModel()

{

}

/// <summary>

/// Public constructor that captures a list of files.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="fi">FileInfo to grab file information from</param>

public FileViewModel(FileInfo fi)

{

_data = fi;

}

}

As you can see, it is very simple – it is simply a wrapper around a piece of data, a FileInfo that represents a file on disk. It exposes properties that are data bindable. There is one element (MarkerFile) that I want you to ignore for a moment – we’ll get to it in a second. Notice that it extends SimpleViewModel. This is one of three primary VM classes in the MVVM helper library. SimpleViewModel is intended for cases where you need the bare minimum support – specifically support for INotifyPropertyChanged. No other services are provided by this base class, and as such it is very light. Let’s look at the directory class next:

/// <summary>

/// Sample ViewModel that wraps a Directory.

/// </summary>

public class DirectoryViewModel : ViewModel

{

/// <summary>

/// String used to send message to main view model about directory selection.

/// </summary>

internal const string SelectedDirectoryChangedMessage = @"SelectedDirectoryChanged";

/// <summary>

/// Marker directory that signals expansion of the tree.

/// </summary>

internal static DirectoryViewModel MarkerDirectory = new DirectoryViewModel();

private bool _isSelected, _isExpanded;

private readonly DirectoryInfo _data;

private readonly ObservableCollection<FileViewModel> _files;

private readonly ObservableCollection<DirectoryViewModel> _subdirs;

/// <summary>

/// Name of the directory

/// </summary>

public string Name

{

get { return _data.Name; }

}

/// <summary>

/// Full path + name of the directory

/// </summary>

public string FullName

{

get { return _data.FullName; }

}

/// <summary>

/// True/False whether the directory is selected (i.e. current).

/// Selecting the directory causes it to populate it's file collection.

/// </summary>

public bool IsSelected

{

get { return _isSelected; }

set

{

if (_isSelected != value)

{

_isSelected = value;

if (_isSelected)

{

if (_files.Count == 1 && _files[0] == FileViewModel.MarkerFile)

{

_files.Clear();

_data.GetFiles()

.Where(f => (f.Attributes & (FileAttributes.Hidden | FileAttributes.System)) == 0)

.ForEach(f => _files.Add(new FileViewModel(f)));

OnPropertyChanged("TotalFiles", "TotalFileSize");

}

SendMessage(SelectedDirectoryChangedMessage, this);

}

else

{

_files.Clear();

_files.Add(FileViewModel.MarkerFile);

}

OnPropertyChanged("IsSelected");

}

}

}

/// <summary>

/// True/False if the directory is expanded. Expanding the directory causes it

/// to fill it's subdirectory collection.

/// </summary>

public bool IsExpanded

{

get { return _isExpanded; }

set

{

if (_isExpanded != value)

{

_isExpanded = value;

if (_isExpanded)

{

if (_subdirs.Count == 1 && _subdirs[0] == DirectoryViewModel.MarkerDirectory)

{

_subdirs.Clear();

_data.GetDirectories()

.Where(d => (d.Attributes & (FileAttributes.Hidden | FileAttributes.System)) == 0)

.ForEach(d => _subdirs.Add(new DirectoryViewModel(d)));

}

}

// Throw them away to recollect later - implements a refresh.

else

{

_subdirs.Clear();

_subdirs.Add(DirectoryViewModel.MarkerDirectory);

}

}

OnPropertyChanged("IsExpanded");

}

}

/// <summary>

/// List of files in this directory.

/// </summary>

public IList<FileViewModel> Files

{

get { return _files; }

}

/// <summary>

/// List of subdirectories in this directory.

/// </summary>

public IList<DirectoryViewModel> Subdirectories

{

get { return _subdirs; }

}

/// <summary>

/// Count of files in this directory.

/// </summary>

public int TotalFiles

{

get { return _files.Count; }

}

/// <summary>

/// Total size of all files in this directory.

/// </summary>

public long TotalFileSize

{

get { return _files.Sum(file => file.Size); }

}

/// <summary>

/// Constructor for the marker directory. This is used to detect an expansion.

/// </summary>

private DirectoryViewModel()

{

_data = null;

}

/// <summary>

/// Public constructor

/// </summary>

/// <param name="di">DirectoryInfo to pull information from</param>

public DirectoryViewModel(DirectoryInfo di)

{

if (di == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("di");

_data = di;

_files = new ObservableCollection<FileViewModel> {FileViewModel.MarkerFile};

_subdirs = new ObservableCollection<DirectoryViewModel> {DirectoryViewModel.MarkerDirectory};

}

}

This file is a bit more complicated – like the FileViewModel, this wraps a simple data object (a DirectoryInfo in this case). Notice that it too exposes properties to provide access to various bits of information. Here you can see that it is creating new properties such as TotalFileSize which is the sum of all the files sizes in this directory. That’s one of the jobs of the ViewModel – to provide easily bindable properties for the bits of information we want to display. In this case, the TotalFiles and TotalFileSize gets displayed in the StatusBar of the window when the directory has files.

Notice that the directory exposes files and subdirectories in ObservableCollections – but they are delay populated. This is done so that the TreeView comes up quickly and we don’t have to enumerate the entire disk to retrieve the directories and files! When you expand and collapse the nodes in the tree, it is populating the data. This is done through the IsExpanded property – if you look back in the View, you will see that the TreeView actually binds the TreeViewItem.IsExpanded to this property:

<TreeView Grid.Column="0" ItemsSource="{Binding RootDirectory}"

ItemTemplate="{StaticResource DirectoryTemplate}">

<TreeView.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="TreeViewItem">

<Setter Property="IsSelected" Value="{Binding IsSelected, Mode=TwoWay}" />

<Setter Property="IsExpanded" Value="{Binding IsExpanded, Mode=TwoWay}" />

</Style>

</TreeView.ItemContainerStyle>

</TreeView>

Notice it also binds up the IsSelected property – this is when we populate the files collection. Since they are observable, they will force the UI to update when new items are added or removed and we see the Explorer effect we desire.

Lastly, before we leave this file, notice that when a directory is selected, it makes a method call to a function called SendMessage:

SendMessage(SelectedDirectoryChangedMessage, this);

It passes a string (the key) and an object (the data). This is a built-in service of the ViewModel base class and it’s the reason why this ViewModel does not derive from SimpleViewModel, but instead from ViewModel which is the full version. One of the services provided is a Message Mediator. This service basically allows you to loosely couple various objects together – we’ll see how the target registers, but for now, just notice the sender – it passes a string key and an object. Any target registered for the given key will receive the object. There are several overrides for the message mediator which I’ll detail in a later post.

Ok, let’s switch to the final file – the MainViewModel:

public class MainViewModel : ViewModel

{

private DirectoryViewModel _selectedDirectory;

/// <summary>

/// Root directory - can be bound to an ItemsControl on the UI.

/// </summary>

public DirectoryViewModel[] RootDirectory { get; private set; }

/// <summary>

/// Selected (active) directory

/// </summary>

public DirectoryViewModel SelectedDirectory

{

get { return _selectedDirectory; }

set

{

_selectedDirectory = value;

OnPropertyChanged("SelectedDirectory");

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Command to display the About Box.

/// </summary>

public ICommand DisplayAboutCommand { get; private set; }

/// <summary>

/// Command to end the application

/// </summary>

public ICommand CloseAppCommand { get; private set; }

/// <summary>

/// Main constructor

/// </summary>

public MainViewModel()

{

// Register this instance with the message mediator so it can receive

// messages from other views/viewmodels.

RegisterWithMessageMediator();

// Create our commands

DisplayAboutCommand = new DelegatingCommand(OnShowAbout);

CloseAppCommand = new DelegatingCommand(OnCloseApp);

// Fill in the root directory from C:

RootDirectory = new[] {new DirectoryViewModel(new DirectoryInfo(@"C:")) {IsSelected = true}};

}

/// <summary>

/// This method closes the application window.

/// </summary>

private void OnCloseApp()

{

// Ask the view to close.

RaiseCloseRequest();

}

/// <summary>

/// This method displays the About Box.

/// </summary>

private void OnShowAbout()

{

// Get the message visualizer service from the service resolver.

// All services can be replaced, so make sure to check if we have something

// registered.

IMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer = Resolve<IMessageVisualizer>();

if (messageVisualizer != null)

{

// Show a message box.

messageVisualizer.Show("About File Explorer Sample", "File Explorer Sample 1.0", MessageButtons.OK);

}

}

/// <summary>

/// This method is invoked by the message mediator when a DirectoryViewModel is selected.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="newDirectory">DirectoryViewModel that is now active</param>

[MessageMediatorTarget(DirectoryViewModel.SelectedDirectoryChangedMessage)]

private void OnCurrentDirectoryChanged(DirectoryViewModel newDirectory)

{

SelectedDirectory = newDirectory;

}

}

Here you can see the same basic principle – it exposes properties the UI binds to. In particular here we see Commands being exposed as properties. Commands is what drives a UI – it allows a UI to trigger actions in the ViewModel. We are using two basic commands here – CloseAppCommand and DisplayAboutCommand. If you look at the constructor, you will see they are backed by a DelegatingCommand object. This is a common pattern found in almost every MVVM framework out there, but it’s essentially a pair of delegates that are called when the command is checked and when it is invoked. In our cases here, we always allow the command to execute so we only provide the execution handler (a second parameter would define the typical CanExecute handler). There are a couple of overrides for this object as well – one that provides type safety for the parameter and one that always uses object and allows for any object as data. Again here we are being simple and not using any parameters so our bound methods are both no-parameter methods.

The CloseAppCommand command invokes the OnCloseApp method – which in turn calls RaiseCloseRequest. This JulMar ViewModel method will close the view associated with the ViewModel if you associated the two using the ViewModelCreator.

The OnShowAbout method is called by the DisplayAboutCommand. It uses another registered service in the library called IMessageVisualizer. The message visualizer is used to display a simple message box from the ViewModel. Here we use it to display an about box. There are several other services I’ll talk about in the next post.

Notice that the RootDirectory property which is data bound to the TreeView.ItemsSource is exposes as an array – this is because the TreeView always expects a collection of items even though we always have a single root item. So we wrap a single DirectoryViewModel into a collection and return it as the property.

If you look at the end of the file you will find our message mediator target – OnCurrentDirectoryChanged. We use this as a way to see when a new directory has been selected in the tree. For a ListBox, we could have just data bound the SelectedItem to the property, but TreeView isn’t a selector and doesn’t expose a SelectedItem property. Instead you either have to catch an event (I’ll show how you can do that in a future blog entry about the MVVM helpers library) or use this little mediator trick.

The [MessageMediatorTarget] attribute is the secret sauce here – it tells the message mediator to wire this method up to the passed string key. When that key is used in a SendMessage call and the parameter type is a DirectoryViewModel (or derived type), the mediator will invoke this method. This all happens without any direct linkage between the DirectoryViewModel and the MainViewModel. The delegate instance is held in a weak reference so there’s no concern for memory leaks.

The second part of the magic is in the constructor – the message mediator is an opt-in service, so notice the call to RegisterWithMessageMediator(). This is what causes this instance to be noticed by the mediator. There is a balancing UnregisterWithMessageMediator if you ever want to unhook the instance. You can also use methods to directly wire up handlers (without attributes). This is useful when you are dynamically linking things together at runtime vs. compile time.

Well, that covers the basics of the framework Views + ViewModels. In the next post, I will detail the service registration and basic service mechanism that’s built into the framework for you to use. Until then, ciao!