Replacing Services in MVVM Helpers

One of the key features in any good library is to provide a wide set of services for applications to use, but also some level of flexibility to replace those services when the built-in implementation aren’t what is needed.

MVVM Helpers provides this capability using the Managed Extensibility Framework (MEF) which is built into .NET 4.0 and provided on http://mef.codeplex.com for .NET 3.5. MEF allows you to compose your application dynamically – looking up concrete implementations for interfaces or base classes through a set of registered catalogs. MVVM Helpers automatically registers the current AppBase directory (where the .EXE loads from) as the primary catalog directory and puts all the JulMar assemblies at the end of the search list. This allows the application to replace any service except MEF itself. In addition, one of the features added to MVVMHelpers 4.03 was the ability to add other search paths (extension directories for example).

As an example, let’s build a simple application that uses the built-in IMessageVisualizer and INotificationVisualizer services.

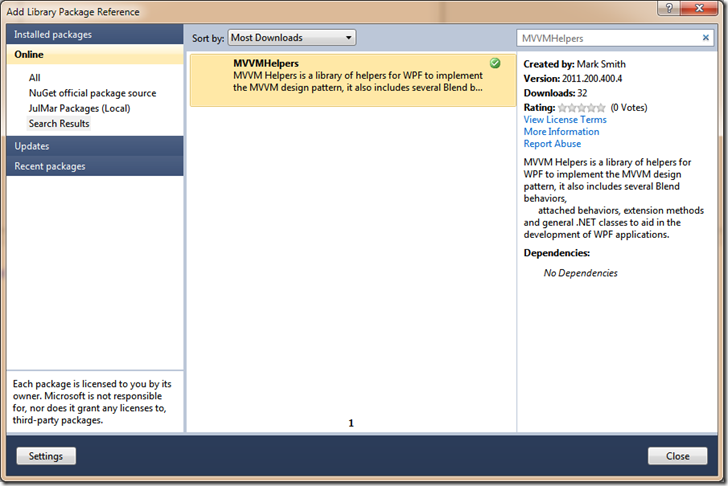

I’ll start with a brand-new WPF application and add MVVMHelpers through NuGet – a new service from Microsoft for adding dependencies easily:

Next, let’s add a single button and a TextBlock to the window, in two equally spaced rows – binding the first to a command called “CalculatePi” and the second to some text “PiText”.

<Grid>

<Grid.RowDefinitions>

<RowDefinition />

<RowDefinition />

</Grid.RowDefinitions>

<Button Content="Do Some Long-Running Work" Command="{Binding CalculatePi}"

HorizontalAlignment="Center" VerticalAlignment="Center" Padding="10,5" />

<TextBlock Text="{Binding PiText}" Foreground="Blue" FontSize="16pt" Grid.Row="1"

HorizontalAlignment="Center" VerticalAlignment="Center" />

</Grid>

Next, we’ll create a new ViewModel, I’ll name it MainViewModel to hold these two data elements (an ICommand and a string). In the sample I’m using the ViewModelCreator extension to bind the View and the ViewModel, but you could use your technique of preference – here’s my markup:

<Window x:Class="ServiceReplacement.MainWindow"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

xmlns:julmar="http://127.0.0.1:8080/wpfhelpers"

xmlns:ViewModels="clr-namespace:ServiceReplacement.ViewModels"

DataContext="{julmar:ViewModelCreator ViewModelType={x:Type ViewModels:MainViewModel}}"

Title="MainWindow" Height="350" Width="525">

In the new MainViewModel class, I’ll first derive it from the JulMar.Mvvm.ViewModel base class – I do this because that class exposes everything from it’s base SimpleViewModel, but also provides direct access to the service resolver through a Resolve<T> method. Next, I’ll add the two properties and stub out the command:

public class MainViewModel : ViewModel

{

public ICommand CalculatePi { get; private set; }

private string _piText;

public string PiText

{

get { return _piText; }

set

{

_piText = value;

OnPropertyChanged(() => PiText);

}

}

public MainViewModel()

{

CalculatePi = new DelegatingCommand(OnCalculatePi);

}

private void OnCalculatePi()

{

}

}

Notice the use of the expression tree version of OnPropertyChanged – you can pass a compile-safe expression to indicate a specific property has changed (or use the string text, or pass nothing to indicate everything has changed). As always, pick the variety you prefer. Now, let’s provide a long-running operation in our OnCalculatePi method, we’ll use a new Task (new to .NET 4.0):

Task.Factory.StartNew(() => { Thread.Sleep(5000); PiText = Math.PI.ToString(); });

Here we will wait for 5 seconds, and then populate our PiText property with the text. Ok, now that we’ve got all that out of the way, let’s use the IMessageVisualizer service to make sure the user really wants to calculate PI. Recall the interface:

public interface IMessageVisualizer

{

MessageResult Show(string title, string message, MessageButtons buttons);

}

This is then implemented internally by MVVM Helpers as a MessageBox.Show. We’ll add this as a single test up-front.

private void OnCalculatePi()

{

IMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer = Resolve<IMessageVisualizer>();

var result = messageVisualizer.Show("Calculating Pi",

"This operation takes a long time. Are you sure you want to proceed?",

MessageButtons.YesNo);

if (result == MessageResult.Yes)

{

Task.Factory.StartNew(() =>

{

Thread.Sleep(5000);

PiText = Math.PI.ToString();

});

}

}

Note that we could also use the following as a field in our class – this would be injected by MEF as part of the view construction.

[Import]

IMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer;

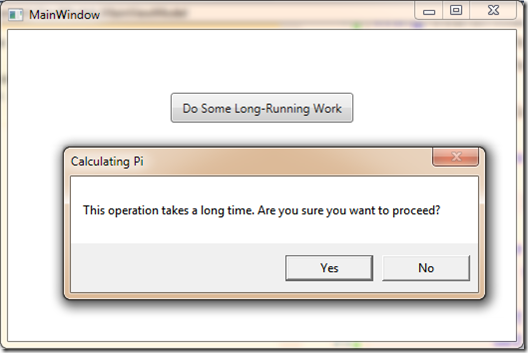

Here’ we’ll just use the Resolve<T> method, but if you prefer Dependency Injection the above works nicely. Running this, produces the expected result:

Next, just to flesh this out, let’s add a call to the INotificationVisualizer to provide feedback that an operation is proceeding – recall the interface for this:

public interface INotificationVisualizer { IDisposable BeginWait(string title, string message); }

You call BeginWait to start a notification – it returns an IDisposable element, once you are done waiting, you dispose that object and the notification is destroyed. The built-in implementation simply provides an hourglass while it’s running – no visualization is actually produced by default. We can add this into our task fairly easily through a continuation:

private void OnCalculatePi()

{

IMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer = Resolve<IMessageVisualizer>();

var result = messageVisualizer.Show("Calculating Pi",

"This operation takes a long time. Are you sure you want to proceed?", MessageButtons.YesNo);

if (result == MessageResult.Yes)

{

IDisposable waitNotify = Resolve<INotificationVisualizer>().BeginWait("Working", "Calculating Pi.. Please Wait");

Task.Factory.StartNew(() =>

{

Thread.Sleep(5000);

PiText = Math.PI.ToString();

}).ContinueWith(t => waitNotify.Dispose(), TaskScheduler.FromCurrentSynchronizationContext());

}

}

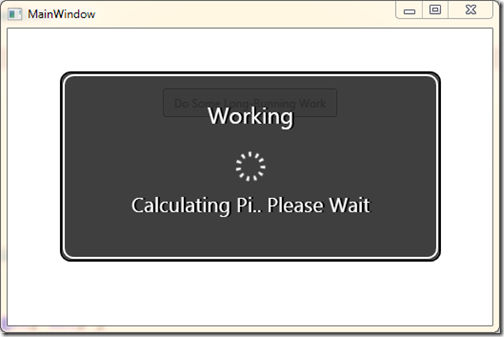

Running this will produce an hourglass while we are waiting for the operation to complete – perfectly reasonable, but perhaps not what we want in this case. Let’s say for example that we’d like a transparent dialog to be displayed with a spinning wait indicator:

This is easily done once you understand the service registration process. Recall that I mentioned that MVVM Helpers places the JulMar assemblies (Julmar.Core, Julmar.Helpers and JulMar.Behaviors) last in the service chain. This simply means that any registered implementation of a service that MEF finds first will be used in place of the default implementation in the MVVM Helpers libraries. It’s actually very easy to do:

As a first step, we need to add a reference to System.ComponentModel.Composition – this is used already (as it’s where all the MEF code lives), but in order to expose our own service implementations we need to explicitly add a reference to the application. Replacing a service is really done by providing an implementation for the given service interface (INotificationService in this case) and then adding an [ExportService] attribute to the implementation.

[ExportService(typeof(INotificationVisualizer))]

class NotificationVisualizer : INotificationVisualizer

{

public IDisposable BeginWait(string title, string message)

{

... code goes here ...

}

}

By simply making sure this class is in an assembly that is placed in the AppBase (where your .EXE lives), it will get used anytime something requests the INotificationVisualizer. The implementation provided in the sample code displays a notification dialog – where the IDisposable returned object closes the dialog for you. The cool part of this is you don’t change anything in your ViewModel code – it simply invokes the same notification service, but now a dialog is displayed while we are busy sleeping on Pi..

You can use this technique for any of the built-in services, or even use it to create your own services – I often add a logging service for example:

public interface ITraceService

{

void Trace(TraceEventType traceType, string data);

void Trace(TraceEventType traceType, string format, params object[] data);

...

}

I place this interface in some common base assembly that everything in my solutions shares, and then provide an implementation in the main application project -

[ExportService(typeof(ITraceService))]

class TraceService : ITraceService

{

private readonly TraceSource _traceSource;

public TraceService()

{

_traceSource = new TraceSource("app.trace");

}

public void Trace(TraceEventType traceType, string data)

{

_traceSource.TraceEvent(traceType, 0, data);

}

public void Trace(TraceEventType traceType, string format, params object[] data)

{

_traceSource.TraceEvent(traceType, 0, format, data);

}

...

}

This then makes the service available through the service locator automatically – no need to register or do anything tricky with it. If you’d like to place your services and extensions (such as UI visualization) into another directory, you can do that as well – just make sure to add a catalog as part of your application constructor. For example – if you want to use the folder “Extensions” for all your add-ins, you can add the directory through the Application constructor:

public App()

{

MefComposer.Instance.AddCatalogResolver(new DirectoryCatalog("Extensions", "*.dll"));

}

This tells MEF to search the given catalog for dependencies as well – again, it will be searched before the Julmar core assemblies. Just make sure the directory actually exists or MEF will throw an exception during the first composition (when the MainWindow comes up).

You can also use MEF directly if you choose to have complete control over the catalog structure.

Hopefully that gives some background on service resolution – the full sample is located here.

Happy Coding!