Unit Testing with services in MVVM Helpers

In the previous post I showed how you can easily replace services within your application to fit whatever your goals are. This is also a requirement when you would like to unit test your application, but there’s a slightly different twist to it.

As a simple example, let’s use the little demo app we built to play with service replacement. In this case, our CalculatePi method in the MainViewModel ended up with the following code:

private void OnCalculatePi()

{

IMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer = Resolve<IMessageVisualizer>();

var result = messageVisualizer.Show("Calculating Pi",

"This operation takes a long time. Are you sure you want to proceed?",

MessageButtons.YesNo);

if (result == MessageResult.Yes)

{

IDisposable waitNotify = Resolve<INotificationVisualizer>().BeginWait("Working",

"Calculating Pi.. Please Wait");

Task.Factory.StartNew(() =>

{

Thread.Sleep(5000);

PiText = Math.PI.ToString();

}).ContinueWith(t => waitNotify.Dispose(),

TaskScheduler.FromCurrentSynchronizationContext());

}

}

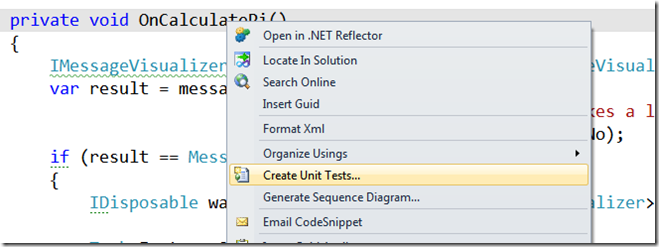

Notice we depend on two things – IMessageVisualizer and IUIVisualizer. When unit testing, we need to either provide these dependencies in some way, or provide alternatives to them. As a starting point, let’s use Visual Studio to generate a unit test (this is not TDD, just basic unit testing as we’ve already written the method!) If you right click on the method, you should find a Create Unit Tests… option:

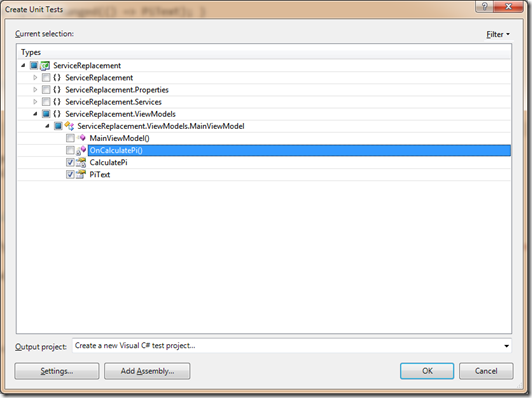

In the resulting dialog, you can choose what you’d like to test. You can test internal (private) methods, or just the public interfaces – however deep you’d like to go. In this case, I’ll choose to test the command and the text produced:

We’ll just quickly make a call to the command, and then verify the text is set to our expected value:

/// <summary>

/// A test for CalculatePi

///</summary>

[TestMethod()]

public void CalculatePiTest()

{

MainViewModel_Accessor target = new MainViewModel_Accessor();

target.CalculatePi.Execute(null);

Assert.AreEqual(Math.PI.ToString(), target.PiText);

}

Now, we have a bit of a problem currently – right now we are relying on the UI services to present a message box and then provide a notification. We clearly cannot use these services when unit testing. So we need some way to replace them specifically for this run – in this case we don’t want to use the [ExportService] attribute, we want to be very explicit.

In this case, what we really want are mock implementations of these services – implementations that track what has been called and return canned responses rather than prompting the user for them. There are several very nice libraries for doing this (see Rhino Mock for my favorite), but to make this clear, let’s provide an actual mocked class for both:

public class MockNotificationVisualizer : INotificationVisualizer, IDisposable

{

public DateTime? LastBeginCall { get; set; }

public DateTime? LastDisposeCall { get; set; }

public IDisposable BeginWait(string title, string message)

{

LastBeginCall = DateTime.Now;

return this;

}

public void Dispose()

{

LastDisposeCall = DateTime.Now;

}

}

public class MockMessageVisualizer : IMessageVisualizer

{

public MessageResult Response { get; set; }

public MessageResult Show(string title, string message, MessageButtons buttons)

{

return Response;

}

}

Notice that we are simply tracking the calls for the notification visualizer – we want to ensure BeginWait and Dispose are both called – and we track when they are called so we can test for ordering. The message visualizer service is mocked out to return a specific response – this let’s us control the code path taken.

Now that we have these implementations we can register them explicitly as part of our test – you can use the [TestInitialize] or [ClassInitialize] if you like, but I prefer to do it on each test so I have access to the underlying fields for other tests. To replace the services, we simply register these mocked objects for the interfaces they are implementing:

[TestMethod()]

public void CalculatePiTest()

{

MainViewModel_Accessor target = new MainViewModel_Accessor();

MockNotificationVisualizer notifyVisualizer = new MockNotificationVisualizer();

MockMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer = new MockMessageVisualizer { Response = MessageResult.Yes };

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Add(typeof(INotificationVisualizer), notifyVisualizer);

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Add(typeof(IMessageVisualizer), messageVisualizer);

target.CalculatePi.Execute(null);

Assert.AreEqual(Math.PI.ToString(), target.PiText);

}

This will add the services to the service resolver (the default one is tracked by the static ViewModel.ServiceProvider property but you can also get it through MEF through an import for the IServiceProvider or IServiceProviderEx interface). Once the test is complete, we can remove the service:

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Remove(typeof(INotificationVisualizer));

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Remove(typeof(IMessageVisualizer));

Now, we can use these implementations to provide testing directives – for example we can ensure BeginWait and Dispose are both called and done in the expected order:

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastBeginCall != null);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastDisposeCall != null);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastDisposeCall > notifyVisualizer.LastBeginCall);

We can also use the message visualizer to force a “No” response – and then ensure the text isn’t set through another test method:

[TestMethod()]

public void DoNot_CalculatePiTest()

{

MainViewModel_Accessor target = new MainViewModel_Accessor();

MockNotificationVisualizer notifyVisualizer = new MockNotificationVisualizer();

MockMessageVisualizer messageVisualizer = new MockMessageVisualizer { Response = MessageResult.No };

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Add(typeof(INotificationVisualizer), notifyVisualizer);

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Add(typeof(IMessageVisualizer), messageVisualizer);

target.PiText = string.Empty; target.CalculatePi.Execute(null);

Assert.AreEqual(string.Empty, target.PiText);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastBeginCall == null);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastDisposeCall == null);

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Remove(typeof(INotificationVisualizer));

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Remove(typeof(IMessageVisualizer));

}

If you are actually following along in code, you might notice that the first test actually fails with an exception – because we have another dependency we haven’t provided for: SynchronizationContext. This is being used in our method to ensure we execute the dispose on the UI thread. The unit testing framework makes no guarantee of the Synchronization Context being present however – unlike WPF. So, we need to provide one for the testing framework to use. Here’s the one I generally use – it has more functionality than what is necessary for this test (in that it supports Posted operations):

public class MockSynchronizationContext : SynchronizationContext

{

readonly List<Tuple<SendOrPostCallback,object>> _postedCallbacks = new List<Tuple<SendOrPostCallback, object>>();

public override void Send(SendOrPostCallback d, object state)

{

d(state);

}

public override void Post(SendOrPostCallback d, object state)

{

lock (_postedCallbacks)

{

_postedCallbacks.Add(Tuple.Create(d, state));

}

}

public void ExecutePostedCallbacks()

{

lock (_postedCallbacks)

{

_postedCallbacks.ForEach(t => t.Item1(t.Item2));

_postedCallbacks.Clear();

}

}

}

Next, to add it we save off the original value and then restore it:

SynchronizationContext savedContext = SynchronizationContext.Current;MockSynchronizationContext mockContext =

new MockSynchronizationContext();SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(mockContext);

target.CalculatePi.Execute(null);

Assert.AreEqual(Math.PI.ToString(), target.PiText);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastBeginCall != null);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastDisposeCall != null);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.LastDisposeCall > notifyVisualizer.LastBeginCall);

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Remove(typeof(INotificationVisualizer));

ViewModel.ServiceProvider.Remove(typeof(IMessageVisualizer));

SynchronizationContext.SetSynchronizationContext(savedContext);

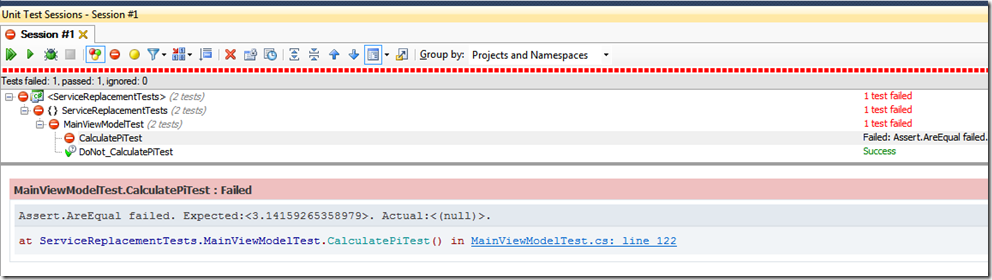

Again, you could place this code into the test initialization or even the class initialization to remove it from each test. Running the test again solves the exception, but it fails:

It might not be obvious why it fails here – recall (look at the implementation code) that the CalculatePi uses a background task to do the work. This returns immediately back to the unit test, which then tries to get the current value for PI – and gets null because the task hasn’t completed yet! Here we want to wait for the Dispose to be called to get the value, or wait for our synchronization context to call back any posted methods. To do that, we’ll modify our mocked implementation slightly to provide a wait method (with timeout) that manages the synchronization context for us:

public class MockNotificationVisualizer : INotificationVisualizer, IDisposable

{

public DateTime? LastBeginCall { get; set; }

public DateTime? LastDisposeCall { get; set; }

readonly ManualResetEventSlim _waitEvent = new ManualResetEventSlim(false);

public IDisposable BeginWait(string title, string message)

{

LastBeginCall = DateTime.Now;

return this;

}

public void Dispose()

{

LastDisposeCall = DateTime.Now;

_waitEvent.Set();

}

public bool WaitForDispose(TimeSpan waitTime, MockSynchronizationContext context)

{

DateTime start = DateTime.Now;

while (DateTime.Now - start < waitTime)

{

if (_waitEvent.Wait(1))

return true;

context.ExecutePostedCallbacks();

}

return false;

}

}

And then add the support to our test:

target.CalculatePi.Execute(null);

Assert.IsTrue(notifyVisualizer.WaitForDispose(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(10), mockContext));

Assert.AreEqual(Math.PI.ToString(), target.PiText);

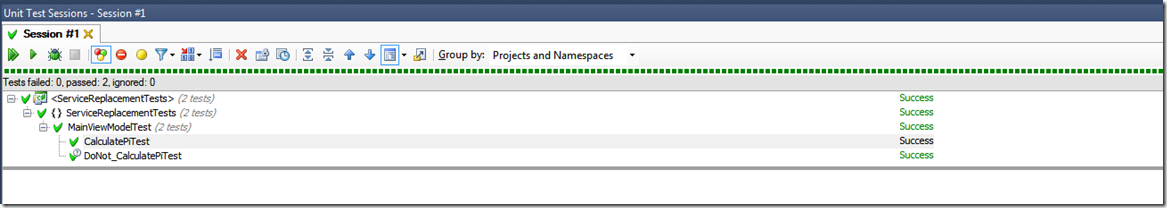

Now, running the tests produces the expected results:

The final solution is available here.

Happy Coding!